Sweeping Yucky LINQ Queries Under the Rug with Expression Tree Rewriting

May 02, 2011 2:06 PM by Daniel Chambers (last modified on May 03, 2011 6:43 AM)

In my last post, I explained some workarounds that you could hack into your LINQ queries to get them to perform well when using LINQ to SQL and SQL CE 3.5. Although those workarounds do help fix performance issues, they can make your LINQ query code very verbose and noisy. In places where you’d simply call a constructor and pass an entity object in, you now have to use an object initialiser and copy the properties manually. What if there are 10 properties (or more!) on that class? You get a lot of inline code. What if you use it across 10 queries and you later want to add a property to that class? You have to find and change it in 10 places. Did somebody mention code smell?

In order to work around this issue, I’ve whipped up a small amount of code that allows you to centralise these repeated chunks of query code, but unlike the normal (and still recommended, if you don’t have these performance issues) technique of putting the code in a method/constructor, this doesn’t trigger these performance issues. How? Instead of the query calling into an external method to execute your query snippet, my code takes your query snippet and inlines it directly into the LINQ query’s expression tree. (If you’re rusty on expression trees, try reading this post, which deals with some basic expression trees stuff.) I’ve called this code the ExpressionTreeRewriter.

The Rewriter in Action

Let’s set up a little (and very contrived) scenario and then clean up the mess using the rewriter. Imagine we had this entity and this DTO:

public class PersonEntity

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

}

public class PersonDto

{

public int EntityID { get; set; }

public string GivenName { get; set; }

public string Surname { get; set; }

}

Then imagine this nasty query (if it’s not nasty enough for you, add 10 more properties to PersonEntity and PersonDto in your head):

IQueryable<PersonDto> people = from person in context.People

select new PersonDto

{

EntityID = person.ID,

GivenName = person.FirstName,

Surname = person.LastName,

};

Normally, you’d just put those property assignments in a PersonDto constructor that takes a PersonEntity and then call that constructor in the query. Unfortunately, we can’t do that for performance reasons. So how can we centralise those property assignments, but keep our object initialiser? I’m glad you asked!

First, let’s add some stuff to PersonDto:

public class PersonDto

{

...

public static Expression<Func<PersonEntity,PersonDto>> ToPersonDtoExpression

{

get

{

return person => new PersonDto

{

EntityID = person.ID,

GivenName = person.FirstName,

Surname = person.LastName,

};

}

}

[RewriteUsingLambdaProperty(typeof(PersonDto), "ToPersonDtoExpression")]

public static PersonDto ToPersonDto(PersonEntity person)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("This method is a marker method and must be rewritten out.");

}

}

Now let’s rewrite the query:

IQueryable<PersonDto> people = (from person in context.People

select PersonDto.ToPersonDto(person)).Rewrite();

Okay, admittedly it’s still not as nice as just calling a constructor, but unfortunately our hands are tied in that respect. However, you’ll notice that we’ve centralised that object initialiser snippet into the ToPersonDtoExpression property and somehow we’re using that by calling ToPersonDto in our query.

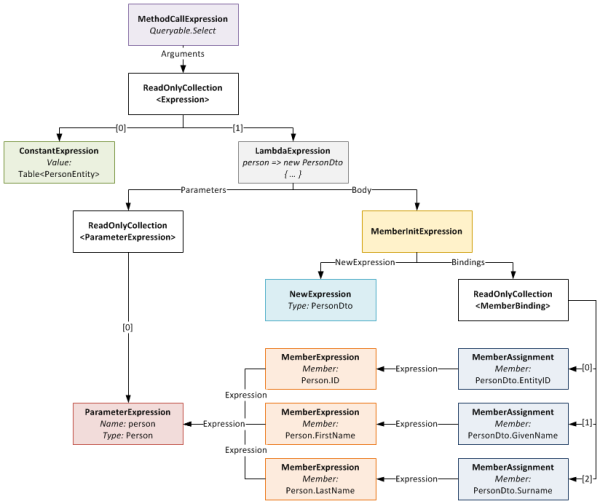

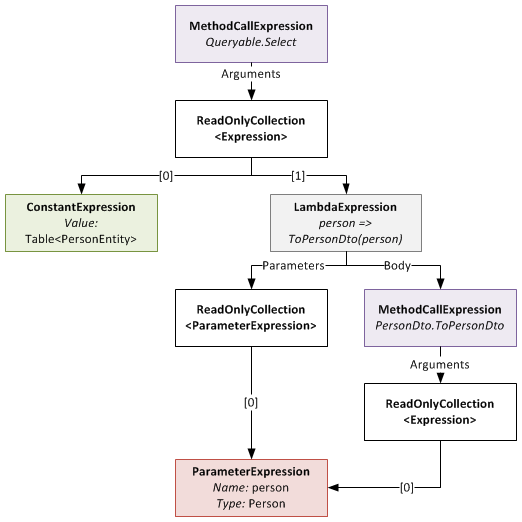

So how does this all work? The PersonDto.ToPersonDto static method is what I’ve dubbed a “marker method”. As you can see, it does nothing at all, simply throwing an exception to help with debugging. The call to this method is incorporated into the expression tree constructed for the query (stored in IQueryable<T>.Expression). This is what that expression tree looks like:

The expression tree before being rewritten

When you call the Rewrite extension method on your IQueryable, it recurs through this expression tree looking for MethodCallExpressions that represent calls to marker methods that it can rewrite. Notice that the ToPersonDto method has the RewriteUsingLambdaPropertyAttribute applied to it? This tells the rewriter that it should replace that method call with an inlined copy of the LambdaExpression returned by the specified static property. Once this is done, the expression tree looks like this:

Notice that the LambdaExpression’s Body (which used to be the MethodCallExpression of the marker method) has been replaced with the expression tree for the object initialiser.

Something to note: the method signature of marker method and that of the delegate type passed to Expression<T> on your static property must be identical. So if your marker method takes two ClassAs and returns a ClassB, your static property must be of type Expression<Func<ClassA,ClassA,ClassB>> (or some delegate equivalent to the Func<T1,T2,TResult> delegate). If they don’t match, you will get an exception at runtime.

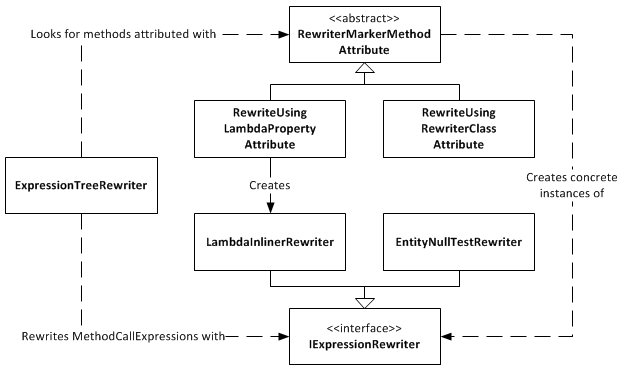

Rewriter Design

Expression Tree Rewriter Design Diagram

The ExpressionTreeRewriter is the class that implements the .Rewrite() extension method. It searches through the expression tree for called methods that have a RewriterMarkerMethodAttribute on them. RewriterMarkerMethodAttribute is an abstract class, one implementation of which you have already seen. The ExpressionTreeRewriter uses the attribute to create an object implementing IExpressionRewriter which it uses to rewrite the MethodCallExpression it found.

The RewriteUsingLambdaPropertyAttribute creates a LambdaInlinerRewriter properly configured to inline the LambdaExpression returned from your static property. The LambdaInlinerRewriter is called by the ExpressionTreeRewriter to rewrite the marker MethodCallExpression and replace it with the body of the LambdaExpression returned by your static property.

The other marker attribute, RewriteUsingRewriterClassAttribute, allows you to specify a class that implements IExpressionRewriter which will be returned to the rewriter when it wants to rewrite that marker method. Using this attribute gives you low level control over the rewriting as you can create classes that write expression trees by hand.

The EntityNullTestRewriter is one such class. It takes a query with the nasty nullable int performance hack:

IQueryable<IntEntity> queryable = entities.AsQueryable()

.Where(e => (int?)e.ID != null)

.Rewrite();

and allows you to sweep that hacky code under the rug, so to speak:

IQueryable<IntEntity> queryable = entities.AsQueryable()

.Where(e => RewriterMarkers.EntityNullTest(e.ID))

.Rewrite();

RewriterMarkers.EntityNullTest looks like this:

[RewriteUsingRewriterClass(typeof(EntityNullTestRewriter))]

public static bool EntityNullTest<T>(T entityPrimaryKey)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Should not be executed. Should be rewritten out of the expression tree.");

}

The advantage of EntityNullTest is that people can look at its documentation to see why it’s being used. A person new to the project, or who doesn’t know about the performance hacks, may refactor the int? cast away as it looks like pointless bad code. Using something like EntityNullTest prevents this from happening and also raises awareness of the performance issues.

Give Me The Code!

Enough chatter, you want the code don’t you? The ExpressionTreeRewriter is a part of the DigitallyCreated Utilities BCL library. However, at the time of writing (changeset 4d1274462543), the current release of DigitallyCreated Utilities doesn’t include it, so you’ll need to check out the code from the repository and compile it yourself (easy). The ExpressionTreeRewriter only supports .NET 4, as it uses the ExpressionVisitor class only available in .NET 4; so don’t accidentally use a revision from the .NET 3.5 branch and wonder why the rewriter is not there.

I will get around to making a proper official release of DigitallyCreated Utilities at some point; I’m slowly but surely writing the doco for all the new stuff that I’ve added, and also writing a proper build script that will automate the releases for me and hopefully create NuGet packages too.

Conclusion

The ExpressionTreeRewriter is not something you should just use willy-nilly. If you can get by without it by using constructors and method calls in your LINQ, please do so; your code will be much neater and more understandable. However, if you find yourself in a place like those of us fighting with LINQ to SQL and SQL CE 3.5 performance, a place where you really need to inline lambdas and rewrite your expression trees, please be my guest, download the code, and enjoy.

Comments (2)

Submit Comment | Comments RSS Feed

Patagonian Toothfish

May 03, 2011 12:10 AM

Nicely done!

Just one little nitpicky comment - the verb form of recursion is 'recur', not 'recurse' :)

Otherwise, a brilliant post...

-J

As a spelling and grammar Nazi myself, I feel honour-bound to fix this. Thanks :)